The transcript below is of a talk was given by Professor Adrian Gregory, the guest speaker at the COSA Annual Luncheon of 2017. It is a comprehensive review of the participation of Old Boys and Staff in the First World War.

‘Since 2014 I have been director of a research network at the university dedicated to ‘Globalizing and Localizing’ the Great War which is based in the Oxford University History Faculty housed in the Old Boys School building on George Street.

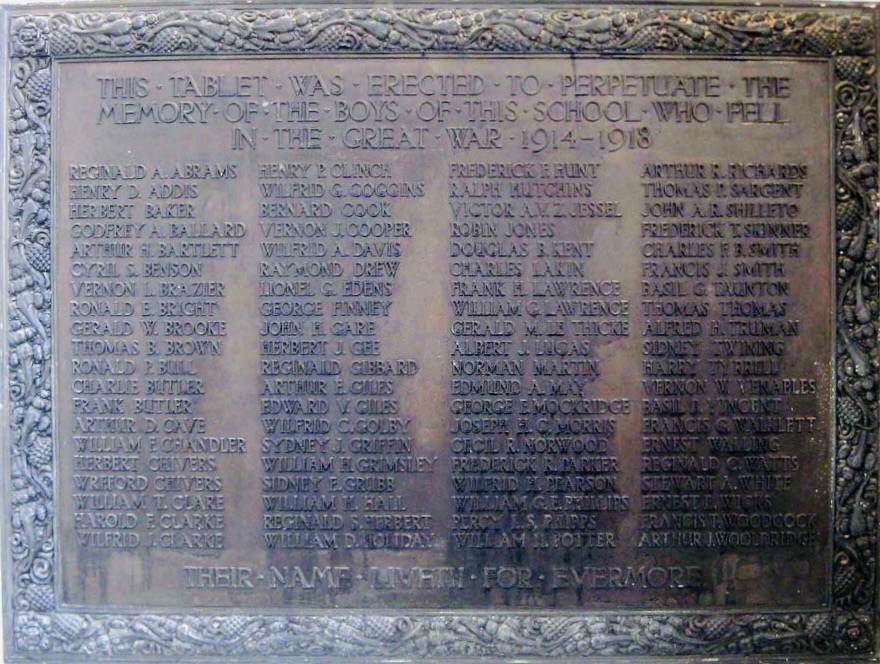

At some point in 2015 I noticed properly for the first time that the School Roll of Service was still hanging on the wall by the main staircase in the building and I started thinking about its significance. In early 2017. I teamed up with the brilliant local historian Liz Woolley (who unfortunately can’t be here today- and who lives literally just down the road in Grandpont) to begin exploring and analysing the Roll.

Rolls of Service

There are tens of thousands of Rolls of Honour for The Fallen in the UK, but full Rolls of Service which list the much larger number of all those who served are significantly rarer. They are also superb historical sources. The City of Oxford Boys High School is a particularly interesting Roll because the school had such an interesting social composition. Much of the research on schools and the First World War has focused on the well documented Public Schools with their well-resourced archives. It is well known that these schools with their prestigious Officer Training Corps and their particular elite ethos contributed a disproportionate number of regular Army officers and early volunteers. But the sheer scale of the First World War meant that wartime leadership could not been limited to the traditional recruiting grounds, particularly after the heavy casualties of the first three years and the crucial second line was the mass of more socially mixed grammar schools of which OHS was such an eminent example. The BEF that emerged victorious in 1918 was predominantly officered by grammar school boys.

Analysis of the COHS Board (I’m deeply indebted to Liz Woolley for the following analysis)

There are 638 names on the Roll of Service of which 618 are pupils and 20 were Masters. This was from a total number of boys who had attended the school of 1,296 in August 1914 rising to 1,583 by November 1918.

Allowing for the fact that some of those who had attended would have died before the war and that the very oldest boys would have been above normal military age these numbers suggest that over half of those of military age during the war served in some capacity. This was slightly above the national average as one might expect from a town with few reserved occupations as the Oxford area had little in the way of heavy industry.

As would seem logical the largest contingent of those who served in the war was amongst those who joined the school between the years 1904 and 1910 and who would have been between the ages of 18 and 25 at the outbreak of the war. Nevertheless there were some who served who had joined the school as early as 1881 and as late as 1917.

78% of those who served had lived in Oxford as pupils and 19% in the rest of the county. Those from Oxford were spread fairly evenly with 101 from the centre, 143 from North Oxford and Summertown, 80 from Jericho, 93 from East Oxford and St Clements, 49 from Grandpont, St Ebbes and New Hinksey.

We have occupational information for the fathers or guardians of 299 of the men. These cover the range from architect and auctioneer to wine merchant and wood carver. The biggest categories were baker, builder, clergyman, clerk, college servant, draper, farmer, schoolteacher, tailor and widow. A tiny number of Dons sent their children, but the bulk of the school was drawn from the city’s middle class with a decent representation of bright working class boys.

From foundation the school had been intended to bridge the gap between Town and Gown and 178 of the OHS boys who served in the war had matriculated with Oxford University. They did so at a total of 23 colleges, the three most popular being St Catherine’s Society, Jesus College and St Johns. A mere 4 went to Cambridge but 35 went to other universities.

550 served in the army, 51 in the RFC/RAF and 29 in the Navy. 8 of those named served as civilians, although this must have massively understated those involved in war work.

54 served in non-British forces, 22 of these in the Canadian forces, 12 in the Indian Army, 8 in the Australian, 3 in the South African 1 each in the New Zealand forces, the Nigerian regiment and the British West Indies Regiment. 3 served in the French Army, 2 in the Belgian and 1 in the American.

310, which was 49% of the OHS boys who served attained commissions.

In total 81 old boys died in the war. This was 12.7%, slightly above the national average. The death rate for officers was slightly higher, 13 % and significantly higher for 2nd lieutenants in the army, the most dangerous rank, of whom 25% died. 116 of those listed (amounting to 18%) were wounded at least once and of these 80 (69%) were officers

57 OHS boys were decorated, being awarded 9 DSOs and 28 MCs (with 3 bars)

How did the school community experience the war?

One question that interests us is how much the war changed the trajectories of pupils lives. A preliminary view seems to be: less than we might think. The profile of post-war employment – mostly in business and public service – doesn’t suggest the war markedly effected social mobility in aggregate either for better or worse but this picture may change as we develop more individual biographical detail.

The OHS Magazine during the war printed many letters from Old Boys serving in the war. These letters illuminate the global nature of the war. So alongside two letters about fighting in France the October 1915 edition of the magazine includes a detailed account by Norman Kent, the Chaplain on the cruiser HMS Kent of the Battle of the Falkland Islands that had been fought in December 1914. It included graphic descriptions of German sailors drowning and ‘our own men dying in agony’.

In December 1916 the Magazine published a letter written in May 1916 by an old boy serving in Mesopotamia where ‘the daily temperature runs between 100 and 125 degrees’. In July 1917 the Magazine published an account of ‘the war by rail and road’ in German East Africa. A letter published in December 1918 by an old boy who was serving with the British Aviation Mission to the United States began with: ‘In the old days of Senior Locals, I remember studying America from a geographical standpoint; to me then it was but a country of names I had to commit to memory’ – which he never believed he would visit. In the same edition another old boy described touring the churches in the old city of Jerusalem where he was serving with the British Army which had captured the city from the Turks in December 1917,

Of course the magazine also published long accounts from participants in the battles of the Somme, Passchendaele and the tumultuous climax of 1918 on the Western Front.

Those still attending the school during wartime continued to study, to take exams, to win scholarships even if –as the magazine mentioned in 1917- the ‘call up’ prevented them from consolidating before going to university. The school collected for war bonds and for charities.

The wider war also came to the school in the form of refugees. The OHS Magazine in December 1916 mentions the nine Serbian Boys being educated at the school who appear to be doing well as, ‘they are bold and brave boys’. Indeed they were – these tough teenagers survivors of the horrific retreat across Albania in winter 1915 and the lethal epidemics in the camps of Corfu in the spring of 1916

The school’s contribution to final victory

For a school of its size, old boys of OHS made up a disproportionate contribution to final victory. The fame of T.E.Lawrence is too great to encompass in such a short talk, but in terms of individual contribution he is in my view overshadowed by James Arthur Salter. Salter of course did not serve in uniform but he is rightly listed on the schools roll of service. In his role as Director of British and, subsequently, allied shipping Salter was one of the most important organizers of allied victory. (His history of Allied Shipping Control can be found online and is a very revealing work). If Lawrence is in some ways a throwback to the romantic vision of war, Salter exemplified the technical and bureaucratic skills that were central to winning a global industrial conflict. What both men had in common was their advance through the meritocratic ethos of the school and they would of course rightly be honoured in the 1920s with houses of the school named after them.

The other two houses were also named after old boys who had contributed to the war effort in very different ways. Professor Arthur Joliffe put his formidable mathematical skills at the service of the Ministry of Munitions and would be mentioned in dispatches, whilst the footballer Arthur Kerry was captain of motorcyclists in the Royal Engineers and received a military MBE.

Of course, it is worth remembering that for a variety of reasons not all Old Boys served. We have not really explored this issue but one famous alumnus is worth mentioning. The poet John Drinkwater spent the war running a Birmingham theatre. He was apparently exempted from military service by ill-health, but the general consensus is that he was opposed to the war and his wartime plays increasingly show anti-war sentiment. His 1917 play x =nothing had a clear pacifist message veiled behind its setting in the Trojan War and his surprise breakthrough hit Lincoln from 1918 showed the statesman agonized about the blood shed even in a righteous cause. Drinkwater had been close to the poets Rupert Brooke and Edward Thomas both of whom had died in the war by the middle of 1917. It is striking that the December 1919 review of Lincoln in the OHS Magazine saw it as an ‘account and explanation of events that have happened in France in the past five years’.

In his somewhat unreliable war memoir written in old age, The Bells of Hell Go Ting a Ling, the OHS old boy Eric Hiscock wrote of his closest school friend Tommy Wheeler, the son of a local butcher who had joined the Royal Naval Air Service and then the RAF and who had survived until November 1918 when he had crashed into the sea not far from Dunkirk. All of the OHS boys of that generation would be aware of friends who had not come back.

At the dedication of the school war memorial in 1920, Oswyn Murray, the President of the Old Boys Club spoke of the thousands of similar ceremonies that were occurring throughout the Empire – he rejoiced that the Old Boys of the School had done their best in bearing the burden and that the Great War had been fought, ‘not only on the playing field but in the classrooms of Oxford High School and in the playgrounds and class rooms of every school in the Empire.’

It is this perspective on the school community at war which we are trying to utililize in a project for the centenary of the Armistice. Liz and I are co-operating with Oxford Spires Academy, the lineal descendant of COHS in today’s Oxford, in order to help their students become aware of their heritage. The history teacher Jackie Watson is working with 13 academy ‘year nine’ pre-GCSE students (more than half are girls!). They have adopted 12 men named on the COHS roll in order to produce an exhibition by the 11th of November. They have been working in various Oxford archives and online to gather information. The students are responding in a variety of ways with art work and literature to tell the stories. It has been fascinating to see them engage with these stories and I think it has been more meaningful to them than the regular national curriculum.’

Professor Adrian Gregory 2017 in association with Liz Woolley