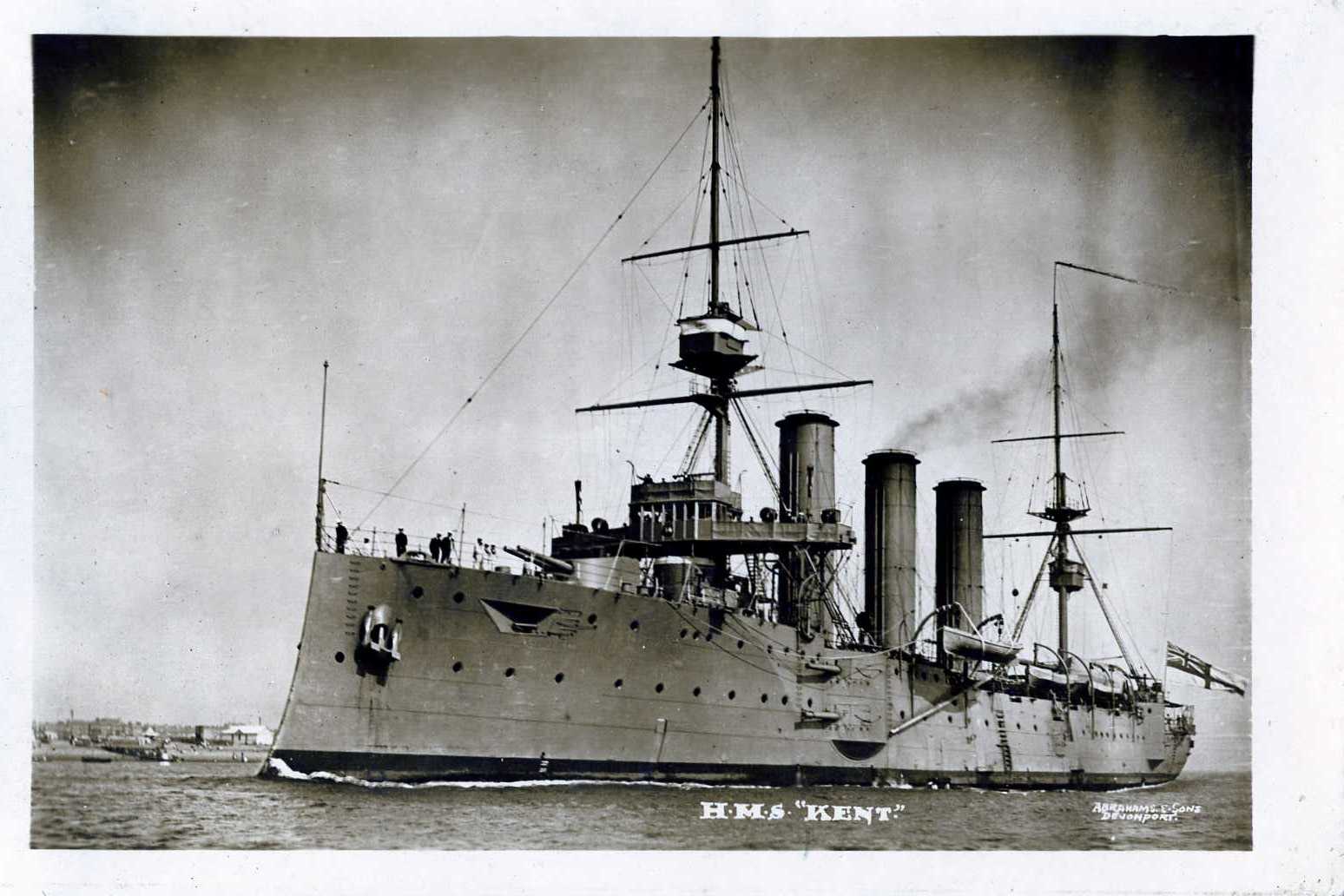

This firsthand account of the World War I Falkland Islands Action on 8th December 1914 was submitted to the OHS magazine by Norman Kent (OHS approx 1891-1898) within four days of the battle and published in 1915 “by permission of the censor”. He was serving as the chaplain on HMS Kent when the conflict erupted.

The battle line-up

| British | German |

| ‘Invincible’ Flagship | ‘Scharnhorst’ Flagship |

| ‘Inflexible’ | ‘Gneisenau’ |

| ‘Kent’ | ‘Nurenberg’ |

| ‘Cornwall’ | ‘Leipsig’ |

| ‘Glasgow’ | ‘Dresden’ |

| ‘Carnarvon’ told off to pick up British Colliers on their way south | |

| ‘Macedonia’ told off to destroy enemy’s Colliers | Two Colliers and Storeships |

| ‘Bristol’ | ‘Seidlitz’ – Armed Merchantman |

The ‘Kent’ had been ordered to act as guardship for the day, with orders to have steam up at 8a.m., ready for putting to sea at a minute’s notice. At 8.20 I went on watch as de-coding officer, and at once heard a rumour that two cruisers, one with four funnels and one with three funnels had been sighted.

I, as usual, discounted the value of the rumour, owing to the extraordinary number of rumours which run round a ship, but I went on the upper deck out of curiosity to see what was doing. I could then see smoke appearing on the hill, but attributed this to peat fires, many of which I had observed the previous day. In the meantime, we had weighed anchor and were slowly proceeding to our station as guardship at the mouth of the harbour. Opinion was divided as to the meaning of the smoke – some attributing it to Japanese ships, and others agreeing with me in thinking that it was caused by peat fires. After a few minutes I went up to the wireless operating room, and discovered that a German wireless message was at that very moment being intercepted and then knew the rumour for once in a way was well-founded.

At about 9a.m. we arrived at the mouth of the harbour (which is more like a Scotch loch than anything else I have seen) and we then saw five cruisers and knew that we were up against the whole German squadron. Immediately appeared the ‘Scharnhorst’, then 17,000 yards away, cleared for action and her guns trained on us. Thereupon the ‘Canopus’, an old battleship with 12-inch guns – moored inside the harbour out of sight but able to fire over a low hill (the guns being directed by telephone from the top of a neighbouring hill) – fired two 12-inch shells.

The Chase

At once the whole German squadron turned tail and went off as hard as they knew how. We proceeded slowly after them, in order to give the rest of our squadron time to weigh anchor and get up steam. At about 9.30 the ‘Glasgow’ came out and passed us going at 25-27 knots. Very soon after she was followed by the ‘Invincible’ and ‘Inflexible’, and very soon after that by the ‘Cornwall’ and ‘Carnarvon’. In the meantime two colliers and an armed merchantman had been seen on the other side of the island and the ‘Bristol’ and ‘Macedonia’ were ordered to proceed to the position indicated and destroy the enemy’s colliers.

At 10a.m. the Germans had a lead of about twenty miles on the ‘Kent’. The flagship having signalled that the Germans were dropping mines, we took care not to follow immediately in their wake but kept slightly to port. The chase continued throughout the forenoon, and though we seemed to gain, the distance was so great that it appeared doubtful whether we should catch them up before night set in.

At 1.15 however, the ‘Invincible’ and ‘Inflexible’ opened fire at a range of 17,000 yards, amid tremendous cheers from our ship’s company who crowded on the forecastle guns and other points of vantage. Twenty minutes later the ‘Scharnhorst’ and ‘Gneisenau’ returned the fire, their shots dropping midway between our two big ships. The ‘Nurenberg’ in the meantime, being a faster ship, had gone ahead and had crossed in front of the ‘Scharnhorst’ and ‘Gneisenau’ to join the ‘Leipsig’ and ‘Dresden’, a move which was followed by the ‘Glasgow’ coming across our bows to the starboard of the ‘Dresden’. The three smaller ships also veered to starboard, so that the ‘Cornwall’ – owing to the change of angle – came into line with us. The ‘Carnarvon’, having dropped a long way behind, was ordered to proceed North (our direction was S.S.E.) to escort our colliers (twelve in number) which had been following up down from the North.

During the next one and a half hours we were able to watch the duel between our own two big ships and the two German big ships; and great was our joy when about 3 we suddenly realised we could only see the smoke of one German ship, though the distance was so great that we could not be certain that one was sunk. Subsequently we learnt that the ‘Scharnhorst’ had been sunk about this time, so that our surmise was accurate. In its way this was the most exciting episode in a very eventful day, and one which may not be seen again by anyone during the War, since we could see practically the whole duel between these big four ships.

In the meantime, it seemed increasingly doubtful that we should catch the ships ahead of us. The ‘Kent’ was short of coal and all the wood in the ship that could be utilised was broken up and used for fuel until we attained a speed of over twenty-five knots. This we maintained for some three to four hours. Some idea of what this meant may be gauged from the fact that though our scheduled horsepower is 22,000 we worked up to 27,000 h.p., and we burst all indicators in the engine-room. Our previous record speed was 22.6.

At about 3.45p.m., the ‘Glasgow’ – being a lighter ship and able to steam faster – got within range and opened fire; and we again had the excitement of the beginning of an action in which we hoped to play our part. At 4.20, while we were all watching this, we suddenly saw a shell pitch short of ourselves but clearly intended as a challenge to us and at once we all got to our battle stations; our distance from the ‘Leipsig’ – who had fired on us – being 12,000 yards. In a few moments we got within our range and were able to return the fire of the ‘Leipsig’. After three or four rounds the ‘Cornwall’ signalled to us, ‘You take the left target and leave us the right!’ whereupon we left the ‘Leipsig’ and chased the ‘Nurenberg’, upon which we now seemed to be gaining – we heard later that in forcing the pace she burst three boilers and had to reduce her speed to twenty-one knots – and at 5.09 we opened fire on her at a range of 11,000 yards.

Early in the engagement a shell burst on our upper deck immediately above my head, making us realise very quickly that we had an opponent worthy of us. The firing continued incessantly till 6.45, when it became quite clear we had won and we called upon the enemy to surrender. His answer was to open fire again – the distance now was only 3,000 yards – and we gave her three or four broadsides, so that at 6.55p.m. she hauled down her flag. She was then a blaze of fire forward and obviously sinking. All except two of her guns had been put out of action, and all her electrical apparatus must have been rendered ineffective. We signalled that we would stand by to pick up survivors and came as near to her as was compatible with keeping at a safe angle out of reach of her torpedoes. Our boats were all riddled with holes and unseaworthy but one was hastily patched up with canvas and red lead and, though it was leaking hard, it was lowered.

Casualties

At 7.27 the ‘Nurenberg’ sank and we at once steamed to the spot; and for about two hours did our best to pick up survivors. Many, however, must have been killed in the action, and the cold water (34 degrees Fahrenheit) was too much for most of the remainder. We only managed to find eleven with any life at all in them; and of these, four died on board after vain attempts had been made to resuscitate them. Thus only seven out of a whole ship’s company survived the action. As regards our own losses, a whole gun’s crew, consisting of marines were put out of action by a shell bursting outside their casemate and setting fire to the lyddite ammunition inside. Four men died within two or three hours of the end of the action and all the rest were very severely burnt indeed. In addition, a shell bursting inside the lower deck took away another marine’s legs and another shell bursting on the deck blew a hole in the back of an able seaman: both these men died very soon after the action was over. In addition, another man, while attempting to extinguish the fire, had a piece of shell through his thigh.

Our casualties were six killed and seven severely wounded (six by burns and one by a shell), some of whom are not expected to live [though if their death has not been reported by the time this gets home it may be assumed that they have recovered]. As regards the ship, she was hit many times, but, providentially, in no vital spots. Three or four fires were started by the German shells but water had been running everywhere all day and the mains were pumping up a continual supply of water. The fires were speedily put out. When the casemate took fire, a serious explosion in the ammunition passage was averted by the bravery of a marine who, picking up a burning charge which dropped down the ammunition hoist, carried it away and smothered the flames at great risk to his own life.

Our foretop was shot away, the funnels pierced in about twelve places, and our wireless transmitting apparatus carried away by a shell. As regards our ship’s company, the behaviour of every man on board was magnificent. While we were chasing the enemy, I wrote up my diary to record my feelings upon going into action and I believe my words reflect what every man felt:

‘Excitement prevails, of course, and a sense of relief that our weeks of chasing across the Atlantic are going to meet with their reward. Also, unchristian as it may seem, we want to “give them ‘Monmouth, and ‘Good Hope’!” I wonder how it will end ; we a cannot lose’ – (I here referred to the whole action, and not to our individual effort ) — but many lives must go – and who knows but that ours may be among them? Now that time has come I pray God that we may, one and all, meet bravely and calmly whatever he may have in store for us. “Better love hath no man this, that a man lay down his life for his friend.” What a wonderful inspiration these words are!’

During the action the excitement was of course intense; but we all had our job to do and we all did it. My own, for example, was to do first-aid work, and though the noise was deafening and the flashes of bursting shells and guns firing was nerve-racking, yet curiously enough I never felt afraid but was able to devote my attention quite calmly to what I was doing.

Following the Action

After the action was over, the scenes were heart-rending, drowning men all round the ship with us able to save only a very few and our own wounded in agony. Four died in my arms and I was able to take their last messages and commend their souls to God – but I never wish to do this again. The other two who died, lived for a few hours longer but there was little chance of their surviving their injuries, which were caused entirely by the fire in the casement. The doctors and those helping them were splendid at what all agreed was the most trying time of the whole affair.

The Germans displayed splendid courage. Their guns outranged ours but their shell fire was nothing like as effective. They were game to the end, and when the ship went down a man was seen quite distinctly waving a German flag, an act which in its way was as fine as anything I have heard of. Apparently, they did not know we were in the Falkland Islands and had intended to take possession of the Islands and make use of them as a coaling base. When they saw us, they piled on all steam to get away and, but for the fact that it was an exceptionally beautiful day, we would have lost them. As it was, they could be quite clearly seen the whole time; but they gave us a good run for our money, covering about 180 miles before we caught them. The action took place in longitude 55 degrees W., latitude 53 degrees 30 minutes S.

As I have already mentioned, our wireless transmitting apparatus had been shot away, but we could still receive messages and were delighted to learn that the ‘Invincible’ and ‘Inflexible’ had sunk the ‘Scharnhorst ‘ and ‘Gneiseneau’. The former at about 3p.m. and the latter about 6p.m; and that the ‘Cornwall’ and ‘Glasgow’ had sunk the ‘Leipsig’ about 7p.m. The ‘Dresden’ managed to get away. It was highly interesting to hear the flagship calling us all through the night, without of course getting any reply and ultimately we heard her order the ‘Bristol’ and ‘Macedonia’ to come and look for us.

It made us feel all the more thankful for having pulled through. Having used up all the wood of the ship and nearly all the coal, and with a big hole about two feet square just above the waterline, we could only steam slowly back to the Falkland Islands. We ultimately arrived with less than fifty tons of coal in our bunkers at 3p.m. on Wednesday December 9th, having met the ‘Macedonia’ on her way to look for us. We found that we were the first ship to get home and were not a little pleased to feel that we were the first ship out: the only ship to take on and sink a German ship by ourselves, and the first ship home. Needless to say we got a tremendous reception from the other ships of the squadron and a very welcome message of ‘Well done, “Kent”’ from the Admiral.

We buried our shipmates, together with a stoker P.O. belonging to H.M.S. ‘Glasgow’, on Friday, December 11th. The latter ship not having a Chaplain, I conducted the service, assisted by the Dean. The Cathedral was full, the service being attended by the Admiral and his staff, the Governor and his staff, all the Captains, Navy Officers and men. A large number of wreaths were given by local residents, every available flower of the place being called into use for this purpose. After the end of the service at the graveside the marines fired a couple of volleys and the ‘Last Post’ was sounded by the buglers. I have never attended a more impressive service – made the more impressive, perhaps, by the fact that it was attended entirely by men, there being no room for women in the Cathedral – and it was no shame to those men who could not restrain a tear, partly from a feeling of personal loss and partly from a deep sense of gratitude for our victory and for our preservation from death.

Looking back, one cannot fail to be impressed by the thought that the series of events did not occur by chance only; to us who took a share in them the hand of the Almighty seems to have been stretched out to protect the weak against the strong, to assist us in our task of preserving the independence of little Belgium.

There can be little doubt that the Germans had no knowledge of our presence in the Falklands. It appears that they had been told that one ship only was there, and that they intended to capture the Islands and make use of them as a base. Moreover, if they had chosen any other day, they would have achieved their purpose. For we only arrived at mid-day on Monday and at once started coaling, doing this in rotation owing to the small number of colliers. By Tuesday night the whole squadron would have gone, leaving us to coal during the night and follow on as early as possible next morning. On any other day, therefore, they would have had an easy task. Further, on that particular day the sun shone brightly and the atmosphere was clear, so that the smoke of the German ships could be seen at a great distance.

On Monday it rained and since Wednesday it has rained every day, and there has been a haze in which we should have lost them. Further, it seems a miracle that the ‘Invincible’ and ourselves were not sunk or really badly damaged. We have, for example, thirty-two holes on our starboard side, some of them nearly two feet square, and if we had been full of coal or if the sea had been rough, one of these would have made us unseaworthy, so near was it to the waterline. As it is, we shall be ready for sea again within a week.

Lastly, we only lost eight men to the Germans’ loss of something like 2,500. The prayer for use at sea which we say at ‘Divisions’ every morning has indeed, in our case, been answered; for which thanks be to God!

NORMAN B. KENT, Chaplain, H.M.S. ‘Kent’. 12th December, 1914