A Speech by Mr Churchill

If you have not landed here from that page, you can read about the circumstances of this speech here

“Mr. President: Although more than year has passed since Lawrence was taken from us, the impression of his personality remains living and vivid upon the minds of his friends, and the sense of his loss is in no way dimmed among his countrymen. All feel the poorer that he has gone from us. In these days dangers and difficulties gather upon Britain and her Empire, and we are also conscious of a lack of outstanding figures with which to overcome them. Here was a man in whom there existed not only an immense capacity for service, but that touch of genius which every one recognises and no one can define. Whether in his great period of adventure and command or in those later years of self-suppression and self-imposed eclipse, he always reigned over those with whom he came in contact. They felt themselves in the presence of an extraordinary being. They felt that his latent reserves of force and willpower were beyond measurement. If he roused himself to action, who should say what crisis he could not surmount or quell? If things were going very badly how glad one would be to see him come round the corner.

Part of the secret of this stimulating ascendancy lay of course in his disdain for most of the prizes, the pleasures and comforts of life. The world naturally looks with some awe upon a man who appears unconcernedly indifferent to home, money, comfort, rank, or even power and fame. The world feels not without a certain apprehen-sion, that here is some one outside its jurisdiction; some one before whom its allurements may be spread in vain; some one strangely enfranchised, untamed, untrammelled by convention, moving independently of the ordinary currents of human action; a being readily capable of violent revolt or supreme sacrifice, a man, solitary, austere, to whom existence is no more than a duty, yet a duty to be faithfully discharged. He was indeed a dweller upon the mountain tops where the air is cold, crisp, and rarefied, and where the view on clear days commands all the kingdoms of the world and the glory of them.

Lawrence was one of those beings whose pace of life was faster and more intense than what is normal. Just as an aeroplane only flies by its speed and pressure against the air, so he flew best and easiest in the hurricane. He was not in complete harmony with the normal. The fury of the Great War raised the pitch of life to the Lawrence standard. The multitudes were swept forward till their pace was the same as his. In this heroic period he found himself in perfect relation both to men and events.

I have often wondered what would have happened to Lawrence if the Great War had continued for several more years. His fame was spreading fast and with the momentum of the fabulous throughout Asia. The earth trembled with the wrath of the warring nations. All the metals were molten. Everything was in motion. No one could say what was impossible. Lawrence might have realized Napoleon’s young dream of conquering the East; he might have arrived at Constantinople in 1919 or 1920 with most of the tribes and races of Asia Minor and Arabia at his back. But the storm wind ceased as suddenly as it had arisen. The skies were clear; the bells of Armistice rang out. Mankind returned with indescribable relief to its long interrupted, fondly cherished ordinary life, and Lawrence was left once more moving alone on a different plane and at a different speed.

In this we find an explanation of the last phase of his all too brief life. It is not the only explanation. The sufferings and stresses he had under-gone, both physical and psychic, during the war had left their scars and injuries upon him. These were aggravated by the distress which he felt at what he deemed the ill-usage of his Arab friends Lawrence had never done anything except write this book as a mere work of the imagination, his fame would last in Macaulay’s familiar phrase, “as long as the English language is spoken in any quarter of the globe”. But this was a book of fact, not fiction; and the author was also the commander. When most of the vast literature of the Great War has been sifted and superseded by the epitomes, commentaries, and histories of future generations, when the complicated and infinitely costly operation of ponderous armies are the concern only of the military student, when our struggles are viewed in a fading perspective and a truer proportion, Lawrence’s tale of the revolt in the desert will gleam with immortal fire.

When this literary masterpiece was written, lost, and written again; when every illustration had been profoundly considered and every incident of typography and paragraphing settled with meticulous care; when Lawrence on his bicycle had carried the precious volume to the few – the very few he deemed worthy to read them – happily he found another task to his hands which cheered and comforted his soul. He saw as clearly as any one the vision of air power and all that it would mean in traffic and war. He found in the life of an aircraftsman that balm of peace and equipoise which no great station or command could have bestowed upon him. He felt that in living the life of a private in the Royal Air Force he would dignify that honourable calling and help to attract all that is keenest in our youthful manhood to the sphere where it is most urgently needed. For this service and example, to which he devoted the last twelve years of his life, we owe him a separate debt. It was in itself a princely gift.

If on this occasion I have seemed to dwell upon Lawrence’s sorrows and heart-searchings rather than upon his achievements and prowess, it is because the latter are so justly famous. He had a full measure of the versatility of genius. He held one of those master keys which unlock the doors of many kinds of treasure-houses. He was a savant as well as a soldier. He was an archaeologist as well as a man of action. He was an accomplished scholar as well as an Arab partisan. He was a mechanic as well as a philosopher. His background of sombre experience and reflection only seemed to set forth more brightly the charm and gaiety of his companionship, and the generous majesty of his nature. Those who knew him best miss him most; but our country misses him most of all; and misses him most of all now. For this is a time when the great problems upon which his thought and work had so long centred, problems of aerial defence, problems of our relations with the Arab peoples, fill an ever larger space in our affairs. For all his reiterated renunciations I always felt that he was a man who held himself ready for a call. While Lawrence lived one always felt – I certainly felt it strongly— that some overpowering need would draw him from the modest path he chose to tread and set him once again in full action at the centre of memorable events. It was not to be. The summons which reached him, and for which he was equally prepared, was of a different order. It came as he would have wished it, swift and sudden on the wings of Speed. He had reached the last leap in his gallant course through life.

“All is over! Fleet career,

Dash of greyhound slipping thongs,

Flight of falcon, bound of deer,

Mad hoof-thunder in our rear,

Cold air rushing up our lungs,

Din of many tongues.”

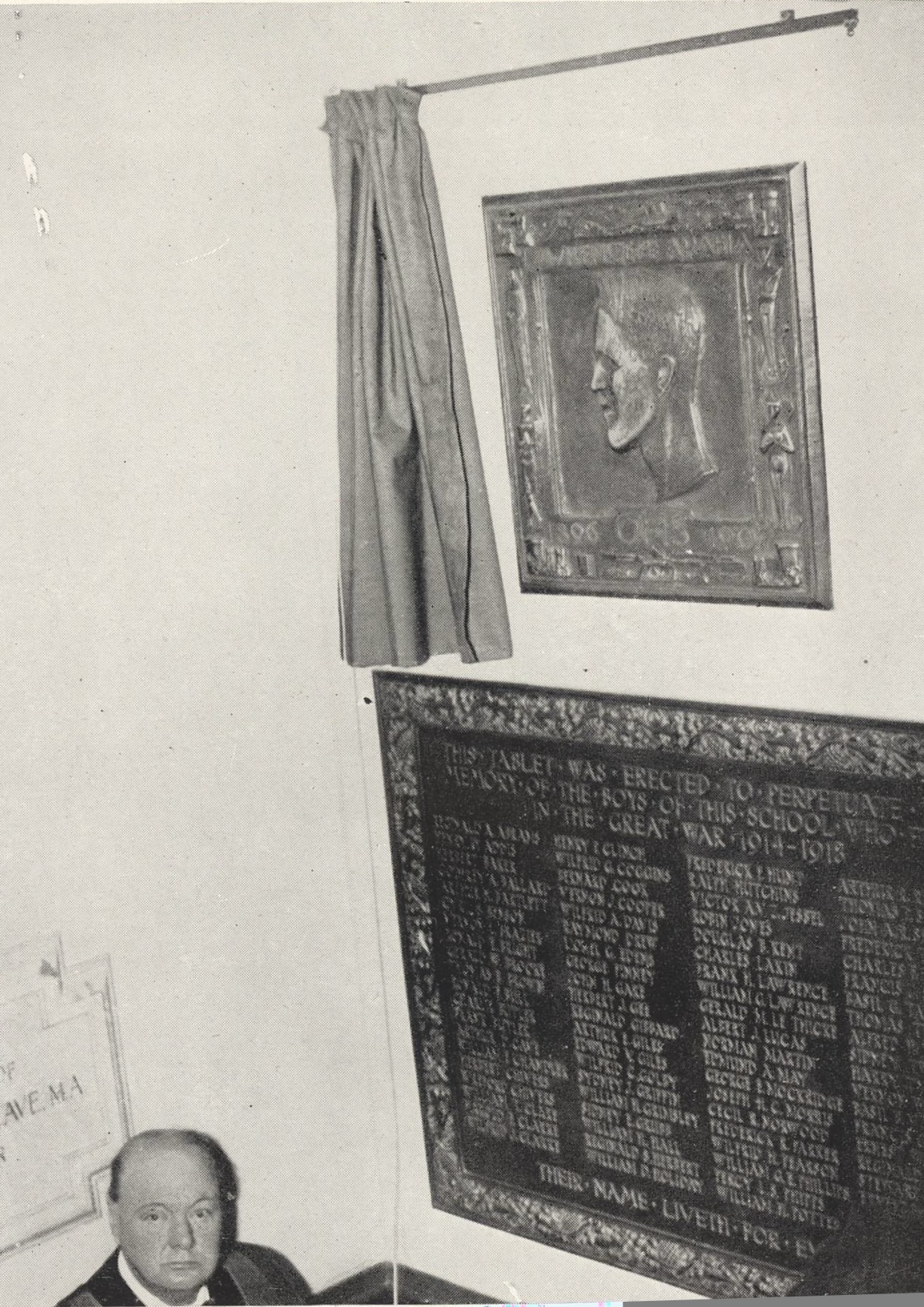

King George the Fifth wrote to Lawrence’s brother, “His name will live in history”. Can we doubt that that is true? It will live in English letters; it will live in the traditions of the Royal Air Force; it will live in the annals of war and in the legends of Arabia. It will also live here in his old school, for ever proclaimed and honoured by the monument we have to-day unveiled.”